![]()

6 May 2021

Matteo Basso’s Perio Sessions offered detailed guide to use of oral antiseptics

Categories:Clinical Practice, Communication, Science

While chlorhexidine remains after many decades the “gold standard” antiseptic in periodontal therapy and maintenance, novel approaches are emerging that may lead to a “paradigm shift” and a more targeted approach to tackling bacteria involved in periodontal diseases.

That was the message delivered by Matteo Basso, adjunct professor of dental ergonomics and management and periodontics and preventive dentistry at the University of Milan (Italy), in an EFP Perio Sessions live webinar on 22 April.

This Curasept-sponsored webinar, “Protocols and practical tips on the usage of oral antiseptics for periodontal therapy and maintenance”, was moderated by EFP past president Filippo Graziani, professor of periodontology at the University of Pisa (Italy), and attended by 118 participants.

Citing a 1999 study published in the British Dental Journal (BM Eley, “Antibacterial agents in the control of supragingival plaque – a review”), Dr Basso outlined the three groups of mouth rinses:

- A: So strong, they can prevent plaque formation to the extent we can use when we cannot perform mechanical hygiene (such as after surgery where there are sutures).

- Examples: Chlorhexidine, acidified sodium chlorate, salifluor, delmopinol.

- B: Less powerful in inhibiting plaque; not a substitute for mechanical hygiene but can be used as a good adjunct.

- Examples: Cetyl pyridinium chloride (CPC), essential oils, triclosan rinses.

- C: Little or no effect on plaque accumulation; mainly have a cosmetic role, such as breath freshening.

- Examples: Sanguinarine, oxygenating agents and saturated pyrimidine, hexetidine.

“When prescribing to a patient we should keep in mind group A, group B and group C, and we should keep in mind their purpose – that is the first thing,” Dr Basso told the webinar. “Evidence suggests that a mouthwash containing chlorhexidine is the first choice, while the most reliable alternative for plaque control is essential oils.”

He observed that in vitro chlorhexidine had the same effect, or even less, when compared with other antiseptics. But in vivo,it is a different story because chlorhexidine has the capacity to last longer in the mouth (up to 12 hours) because of it higher substantivity.

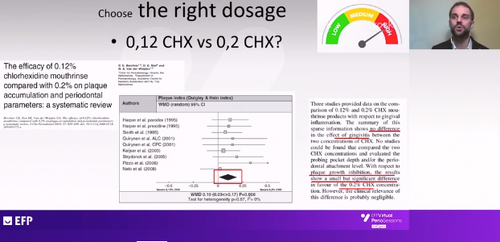

Both in his presentation and in the subsequent question-and-answer session, Dr Basso addressed the question of the right dosage of chlorhexidine. He said that mouthwashes with 0.12% chlorhexidine and those with 0.2% gave similar results in terms of control of gingivitis but there was a statistically significant difference in favour of the stronger dosage in terms of plaque control.

He also discussed products with lower dosages, where chlorhexidine is often combined with other antiseptics (such as CPC), which maybe more suitable for use in longer-term therapies – such as orthodontics. The possible negative interaction between chlorhexidine and sodium lauryl sulphate (SLS) – a common foaming agent in toothpastes – was another topic tackled by the presentation.

Side effects

While the side-effects of chlorhexidine – most notably tooth staining – are not dangerous, “they are not pleasant and they can compromise compliance, which for clinicians is a bad problem,” noted Matteo Basso.

He pointed to possible mechanisms for the problem of staining – degradation of chlorhexidine to release parachloraniline, degradation of salivary proteins, the Maillard reaction, chromogens, and food. He noted that these reactions were normal in the mouth, but normally took place more slowly, so “chlorhexidine is not causing them but accelerating them.”

For instance, in patients who consume many chromogens – contained in red wine, coffee, tea, cola, berries, sweets, and green and red vegetables – the bonding of these chromogens to the tooth surface can be accelerated by chlorhexidine.

Some protocols suggest that using an oxidising mouthwash – peroxyborate or hydrogen peroxide – before using chlorhexidine can reduce staining. While this is effective, said Dr Basso, it requires more compliance from the patient. Another approach involves including polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) in a mouthwash with chlorhexidine at 0.06% – this does produce a significant reduction in tooth staining, but also a significant decrease in the activity of the chlorhexidine.

More recent research (a 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis by Bregje WM Van Swaaj et al.) found evidence that the addition of an anti-discoloration system to chlorhexidine mouthwash “reduces tooth surface discoloration and does not appear to affect its properties with respect to gingival inflammation and plaque scores.”

For some patients, the main problem with chlorhexidine is not the staining but taste alteration. This mainly affects bitter tastes and chlorhexidine is the only known blocker of salty taste in humans. The explanation for this effect is not yet clear but may involve reduced paracellular ion movement. In addition, taste alteration is more common in chlorhexidine mouthwashes with alcohol than in alcohol-free products, and there are differences between different brands.

New approaches

Matteo Basso concluded his Perio Sessions webinar by looking at novel approaches to the control of oral microbial biofilms. He said that chlorhexidine remains the “gold standard” and nothing else offers the same effect and the same benefits, although there are some promising candidates in testing that are not yet in protocols. These include protease inhibitors, quorum-sensing inhibitors, antimicrobial peptides, and probiotics.

He explained how we now know much more about the complexity of the biofilm, the microbiome, and microbiota, which meant that using a “blind” antiseptic risked “killing the good bacteria as well as the bad bacteria”.

He pointed to the “emerging paradigm” which sees the pathogenesis of periodontal and peri-implant disease as the result not of the presence of a single pathogen but as originating in “disturbed homeostasis by dysbiotic microbiota leading to inflammation and slowly eroding the periodontal tissues.

Summing up, Matteo Basso said that if the approach in the past was “just kill ’em all”, the present approach was to maintain a good balance – “We don’t need to destroy everything. We need to keep the patient in balance with his environment and prescribe the patient products for the period the patients need.”

However, the future lies in “co-operating with our microbiome” and working within the complexity of the biofilm to promote the good bacteria so that they “do our job for us”.